Workplaces evolve, and work cultures shift. Some buildings endure as heritage, others quietly disappear. This phenomenon feels endless, almost like an illusion. Yet one question cuts through the haze: what happens when the built environment collides with a world in constant change?

Spaces are not just a backdrop to our lives. They shape how we work, meet one another and feel a sense of belonging. Workspaces reflect our lifestyles, influence their direction and carry our stories. Architect Anis Souissi realised this early in his studies, when he was asked to design a 5×5×5‑metre empty space for two people. Before drawing a single line, he had to imagine a lifestyle and the story within.

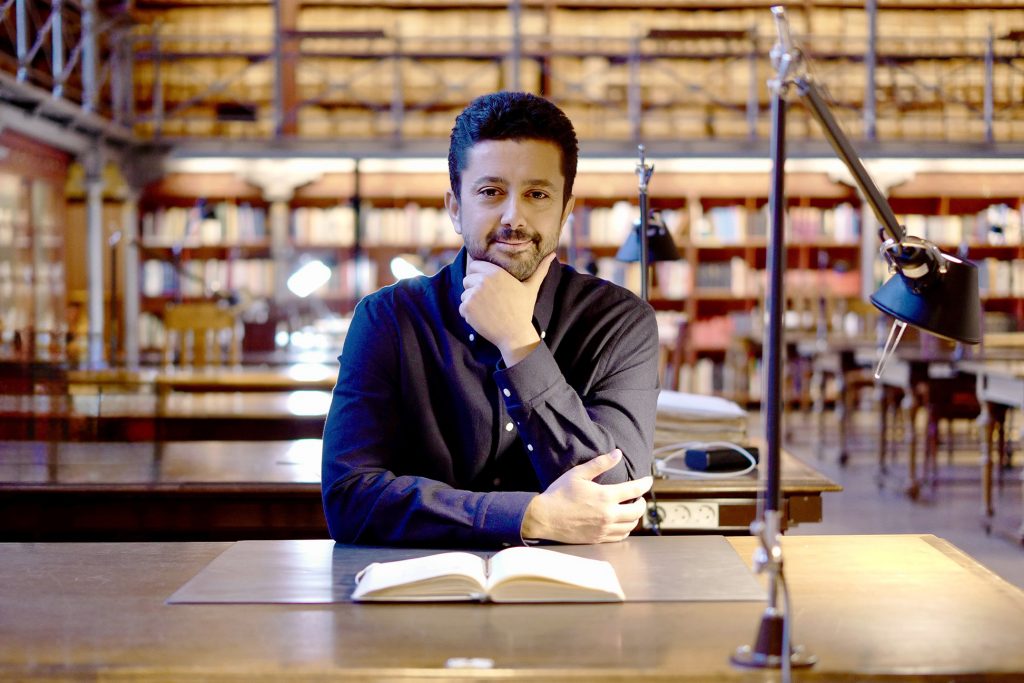

Anis Souissi, Architect SAFA, co-founded the Helsinki based US Architects Ltd with Kalle Ukonlinna.

The exercise revealed a reality that has stayed with him: spaces are never just physical structures. They shape how people experience identity and belonging – and when they shape behaviour, they inevitably shape work. Today, work life is constantly shifting. It is no longer tied to one place but moves with the rhythm of the city and the global world.

The workspace as a cultural lens

As hybrid practices reshape routines, the meaning of “workspace” becomes less about walls and more about what happens between people. The physical environment still matters, but it no longer dictates the rhythm of the day. Instead, it frames the subtle choreography of modern work: moments of focus, interruption, collaboration and retreat.

For Souissi, this shift challenges architects to rethink what a workplace should enable. A space must hold both solitude and connection, structure and improvisation. It must support the individual without isolating them and support the collective without overwhelming it. In his view, the built environment becomes a kind of silent partner in work – shaping behaviour not through instruction, but through atmosphere.

Freedom, fragmentation and the fragile middle ground

Personnel Development Manager Elsi Vuohelainen sees the same tension from inside organisations. Hybrid work has expanded freedom, but it has also made cohesion more fragile. When people move between home, office and everything in between, the question is no longer simply where work happens, but how shared meaning is maintained. Culture becomes something that must be actively nurtured, not assumed.

This is where space and culture intersect. A workspace can encourage encounters, but it cannot force them. It can offer clarity, but it cannot replace trust. The experience of work is shaped by both the tangible and the intangible: the feel of stepping into a room where one person is deep in thought, another asks a question and a third stops to chat; the forgotten post‑it on a desk; the way light hits a table; the movement of air; the subtle cues that help us concentrate, connect and recover.

Hybrid work has become more common in Finland than in many other countries, making Finnish workplaces a kind of living laboratory for how spaces and cultures adapt to change. But the lessons extend far beyond national borders. The most successful environments, physical or digital, are those that recognise a simple truth. Workspaces cannot create culture, but they can either support it or strain it. The challenge now is to design places that provide structure without rigidity, and flexibility without fragmentation.

We think better when we think together

Vuohelainen and Souissi approach workspaces from different angles, yet they share a conviction: an office must be more than a place where tasks are completed. Souissi focuses on the physical environment, and how architecture can spark encounters and support shared thinking. Vuohelainen looks at the shifting realities of remote and hybrid work, where the boundaries of space are constantly renegotiated.

In hybrid work, shared spaces do more than bring people together. They weave ideas into connection, ideas that might otherwise remain apart. Thinking needs room to unfold, not only physically but socially. Research in cognitive science shows that thinking is not a solitary act at all, but something shaped and strengthened through interaction.

It’s no coincidence that Finnish cognitive science and neuroscience have long been drawn to shared thinking, interaction and joint attention. Finnish education and collaborative learning traditions are built on the understanding that insight emerges together. This can create a sense of continuity, even though change is the only constant. The same tension is visible in today’s work environments: they can nurture community, yet must continually adapt to new demands.

Society favors individuality — work thrives on connection

For Elsi, the office is a learning environment. In the photo, Elsi (left) and her colleague Eevi‑Marie Tihinen sift through workshop results, bringing to light what often remains unnoticed.

Hybrid work has exposed a deeper tension: how can individual freedom and collective strength be combined so that they reinforce rather than undermine each other? This question cuts to the heart of trust, how it is built, sustained and carried through shifting work structures.

“Finnish society is highly individualistic, and the interests of individuals are often emphasised in public discourse. It creates challenges for working together. Work communities need more deliberate efforts to clarify shared goals. When some employees are remote and others are in the office, building a sense of community requires active work in both physical and digital environments,” Vuohelainen says.

Finding balance is a societal challenge. Cultures and communities are constantly shaped by new pressures. They rest on interaction, power relations and the needs of groups that do not always align. Historically, the absence of balance has led to conflict, inequality and exclusion. In this light, workspace design becomes part of a broader societal conversation, one that asks how we live, learn and work together in times of continuous change.

Designing for balance in an unbalanced world

The built environment carries the same tensions that shape society itself. Souissi sees architecture as a way to work with these pressures rather than resist them. For him, balance in architecture is not simply a question of visual harmony, but the ability to reconcile human needs with functionality, adaptability and sustainability.

“Balance is a way of holding the big picture and the details side by side. In design, it means seeing a building both as part of the cityscape and as part of people’s everyday lives. It is about how it fits its surroundings and how it feels to use. Every door handle, lighting choice and acoustic surface influences how a space is experienced. When these elements support one another, balance emerges,” Souissi says.

The National Archives of Finland in Helsinki’s Kruununhaka district is, in Anis’ view, a compelling example of timeless architecture. He is drawn to historical, high‑ceilinged spaces that invites reflection and thinking.

When the limits of economic growth meet human reality

The relentless pursuit of economic profit, the overuse of natural resources and ongoing financial pressures all slow down the transition toward sustainable construction. Rising costs and market uncertainty push planning toward quick, cost‑efficient solutions. At the same time, hybrid work is still taking shape. Together, these forces create real challenges for developing work culture. How do we build spaces and practices that endure, support freedom of thought and enable everyday encounters?

As working life changes, a new kind of sensitivity is required in both spatial design and organisational practices. According to Souissi, future architects are not only responsible for designing physical environments. Their role is also to recognise emerging societal phenomena and cultural shifts, to develop responses to them and to propose solutions that evolve organically from one context to another.

Workplace developers face a parallel question: what kinds of spaces foster trust and spark the spontaneous encounters that keep a community alive. The future of working life demands a new spatial mindset, one that looks beyond efficiency to meaning. According to Souissi, spaces must not only organise daily routines; they must give them identity, coherence and a sense of belonging.

Spaces reveal the core of the work culture

While spaces shape how people meet and work together, they also tell a story about the meaning we attach to work. Vuohelainen notes that an organisation’s understanding of spatial planning becomes visible in how well its solutions support everyday practices. Work culture forms through values, people and the small choices that accumulate over time – choices about the encounters a space enables and the atmosphere it creates.

Her thinking points to a broader truth: spaces influence cities only when they genuinely respond to the people who inhabit them.

“Architecture loses its meaning when people’s needs are overshadowed. Design becomes driven by the illusion of egoless freedom or by the repetition of familiar solutions without genuinely analysing new trends or critical insights,” Souissi adds.

“Workspaces support the growth of the urban fabric when they are integrated with housing and culture. This creates lively environments where people’s experiences and values intersect,” says Anis.

Where industrial past meets future work

A clear example of timeless design can be found in the conversion of old industrial buildings, former factories and warehouses, spaces where Souissi has noticed a pattern that had enormous potential for planning the workplaces of the future. These structures carry their own historical identity. Their high ceilings, generous volumes and open floor plans make them inherently flexible, ready to accommodate new forms of work and even new forms of living.

Souissi argues that the same mindset should guide the design of new office buildings and other built environments. From the very beginning, spaces should be conceived with long life cycles and adaptability in mind, so they can respond to the evolving needs and trends of cities decades from now. This raises a broader question about the role of design in shaping working life. Ultimately, design decisions don’t just define the space today. They can prepare us to shape the future itself.

“When designing buildings, we should reflect on the forms of work we want to nurture and the environments that best support them,” Vuohelainen continues.

Spaces are not the same for everyone

Sensitivity means recognising that different tasks require different kinds of spaces. It also means understanding that people experience those spaces differently, depending on the nature of their work and the practices of their community. As philosopher Judith Butler reminds us, spaces are never fully neutral. They shape who feels a sense of belonging and who is pushed to the margins.

Spatial planning is therefore not only practical but also ethical and political. It can reinforce or unsettle role boundaries and influence how identities are formed within a work community. How does this play out in everyday working life, and what does it mean for the people moving through these environments?

“Customer‑facing employees spend their days in video calls, while collaborative work relies on presence and co‑development. The same space can offer freedom, visibility and spontaneity, or it can create stress, noise and constant interruption. Spaces should not force work into a single mould,” Vuohelainen says.

Locality gives spaces their character

Designing spaces requires cultural depth and genuine understanding. Souissi has gained both by living and working internationally, to observe how people shape their buildings and lives in different environments. His time in the Nordic countries and Africa taught him that spaces are defined in big part by climate and locality; even something as simple as the amount of light influences material choices, spatial rhythms and how environments are ultimately used and felt.

“Every architect or designer should stay curious and explore different living environments. Get to know different ways of living and thinking. It guides creative work in a more human direction and broadens the vocabulary of expression, making it better to find the right solution,” Souissi sums up his thinking.

Workspaces caught between promise and change

Working life and architecture are part of the illusion we tell ourselves about what it means to be human. Work gives rhythm to our days, supports our well‑being and offers a reason to seek the next moment of recognition. Finnish modernism, in turn, promised equality and collective prosperity. Today, we are living in a moment of a major transition that will yet reveal where society, and the spaces we work in, are heading. But what do contemporary workspaces actually promise?

Souissi envisions the future of work as a kind of semi‑nomadic everyday life, where people gradually grow into global citizens. He believes that headquarters and collaboration with partners will remain at the heart of shared work, creating synergy and a sense of belonging. At the same time, the possibility of working remotely from different parts of the world brings employees new experiences and perspectives that enrich an organisation’s collective thinking. These influences surface subtly in everyday life.

“When the core of work collaboration is done at the office and part of the work could be done remotely, whether from a summer cottage, while travelling or from home; remote work becomes the freedom and the luxury to occasionally reshape the rhythm of everyday life, and the home can preserve its quality and energy as a safe haven – the peaceful space it has always been,” Souissi reflects, sketching in his notebook as he speaks.

The semi-nomadic future of work

Elsi takes a lunch break in Helsinki’s Hakaniemi Market Hall, where history, entrepreneurship and subtle international influences come together naturally.

The idea of home and work coexisting touches a broader question about the role of cooperation in human life. Collaboration has shaped societies and cultures throughout history. As philosopher Hannah Arendt noted, humanity reveals itself above all in action, and in being together.

Vuohelainen continues this line of thought. She sees the future of working life as more intensive and demanding, yet also more intriguing. Technology pushes us forward, but creativity and the ability to see things differently remain distinctly human qualities. Remote work can make the location of work more flexible, but genuine international cooperation still grows from encounters, shared time and joint processes.

“The world is full of complex problems that no one can solve alone. That is why shared processes and cross‑border interaction become increasingly important. In the working life of the future, we are becoming more and more global citizens,” Vuohelainen reflects.

But work is not only networks and technology. It also requires spaces that support people, and their growth.

What does a space feel like when it understands you?

Perhaps it feels less like being evaluated and more like being supported. Building a new kind of work culture requires spaces that can embrace incompleteness and invite experimentation. It asks us to step aside for a moment, to look from a different angle than those around us. Only then do the hidden layers of work and community begin to reveal themselves.

“Spaces can create togetherness, identity and comfort. They help individuals and the community grow safely,” Souissi says.

Vuohelainen agrees, noting that spaces should anticipate the transformation of working life rather than merely react to it. Yet architecture alone cannot resolve the tension between efficiency and humanity.

“We need a culture that dares to slow down, listen and truly meet one another. Most workspaces are built for performance, not for human interaction. But when the space and the way we work create room for trust, the meaning of work changes entirely. In the end, the real value of a workspace is revealed in whether it helps people find each other and do things no one could achieve alone,” Vuohelainen says, her voice bright with conviction.

Souissi believes that architecture becomes cultural heritage only when it can adapt to future needs and becomes meaningful enough for people to care for it. He speaks of a quality without a name – a feeling that makes a space both alive and enduring, and that helps us let go of previous lifestyles and habits.

“Are we really building today something the future will want to preserve as heritage?” Souissi asks.

The question lingers, an invitation, a challenge, and perhaps the quiet beginning of a new way of imagining work.

****

Text and images: Henni Purtonen

Cover photo taken from the window of US Architects Ltd in Mestaritalo: Anis Souissi

Anis Souissi is a Finnish‑Tunisian architect and a co-founder of the architecture company US Architects Ltd. Previously, he worked as Design Director at ARCO and served as Lead Architect for the Keilaniemenportti project, set to become a new headquarters landmark in Espoo and one of the world’s tallest timber‑hybrid office buildings. Souissi’s work brings together sustainable solutions, cultural heritage and seeks the development of human‑centred urban spaces. In 2023, he was awarded in an international competition for the new Carthage Museum, a UNESCO world heritage site in partnership with OPUS Oy.

Elsi Vuohelainen is Head of Staff Development at the State Treasury of Finland. In addition to competence development, she is passionate about enabling collaboration and fostering well‑functioning work communities. Over the past two decades, she has examined and advanced learning opportunities in working life from the perspectives of both the central government and the higher education sector.